This article was orginally published in the 2020 May/June edition of The The National Watch & Clock Bulletin.

The 2021 NAWCC Ward Francillon Time Symposium, “Horology 1776,” will take place in Philadelphia on October 7–9 at the Museum of the American Revolution. One important speaker on the conference theme of timekeeping during our War of Independence will be Emily Akkermans, curator at London’s Greenwich Observatory. She is one of the women featured in this article, and she will be happy to meet and chat with all who attend. Symposium details and registration can be found at www.horology1776.com.

Horology in England has always been dominated by men. Names like Fromanteel, Harrison, Tompion, Graham, Mudge, Ferguson, Vulliamy, and now George Daniels are on every list of the most famous practitioners, theoreticians, and scholars of our applied science. The founders of London’s Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, who obtained from King Charles I their 1631 charter inscribed on two large richly emblazoned skins of parchment, were all men.

However, in 1715 the Company recognized and sanctioned female apprentices, and some of the first ones are listed on page 155 of Some Account of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers of the City of London compiled by Samuel Elliott Atkins, a former Clerk of the Company, and privately printed in 1881. Top of the roster is Mariane Viet who was “bound” for seven years on January 27, 1715, to her father Claude.

English women’s names also are among the tiny-print 873 pages of Watchmakers and Clockmakers of the World by Brian Loomes, published in 2006, although most were widows and daughters of men in the trade. On page 352 for example, Mrs. Agnes Harrison of Morpeth is listed in 1884 as “Widow of Francis Harrison.” Miss Viet appears here, too, on page 798, with the additional detail that her father had a partner, Thomas Mitchell.

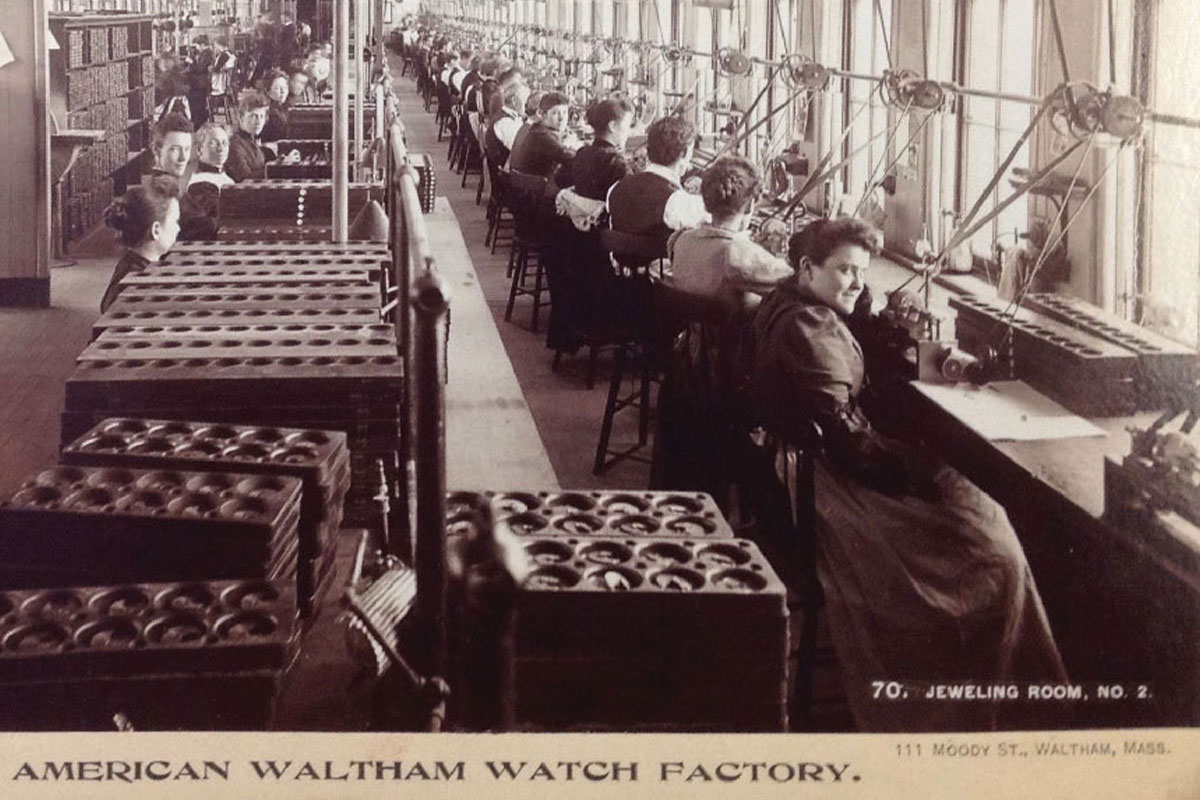

In Colonial America and then in the United States the situation was similar, although we know that from the earliest days of industrialization of clock and watch production, the Massachusetts and Connecticut factories employed large numbers of women. The watch factory in Waltham hired high percentages of women workers (Figure 1), and there were as many in the long multi-story buildings of Seth Thomas, Ingraham, Waterbury, Gilbert, and the rest.

From my research into late 19th-century Boston business records, I also discovered women in the trade there. I examined bound volumes of Married Women in Business 1877 to 1891 that contained hundreds of signed certificates required by city regulations. For example, Hannah Golden Rubin completed and signed a “Certificate of Married Woman Doing Business on Separate Account” confirming that she would be working in “jewelry and watchmaking.” Assistant City Clerk John T. Priest countersigned the form on August 7, 1895, at “3 o’clock, and 30 min.” In August 1905, Emma M. Tebbetts certified that her husband was Charles N. Tebbetts and that she separately would be “manufacturing and selling electric clocks and their accessories.”

This article’s focus is on four London women working in horology today, both at the bench and in curatorial positions. Men previously were in these positions, but these four are not their wives, widows, or daughters, but instead they trained, studied, and were hired solely on skill and merit. I met with each woman while I was in London for two annual horological lectures in November 2019.

Previously, Anna served nine years as a conservator of metalwork and scientific instruments at the Royal Museums Greenwich. She worked with its horological department and trained with the British Horological Institute’s Distance Learning Course. She graduated in 2008 from the University of Sussex with an MA degree in Conservation Studies, and she has a Postgraduate Diploma in Conservation of Fine Metalwork from West Dean College of Arts and Conservation. In May 2019, she was elected to the Council of the Antiquarian Horological Society, which is England’s foremost scholarly horological association.

The Clockmakers Company’s approximately 1,250 books, including many old and rare editions, remain in the London Guildhall complex, on extended loan to the much-larger Guildhall Library that also hosts the 1,700 books on loan by the Antiquarian Horological Society. I met Anna there along with Principal Librarian Peter Ross, who kindly escorted us down into the closed stacks to view both collections on their long rolling shelves.

The books do not circulate outside the building but can be retrieved for researchers seated in the well-lit reading room. Library staff, and Anna, regularly field emailed public inquiries about clocks and watches, but they limit searches and replies to ones that can be handled quickly. People needing more than basic details about a maker or timepiece are encouraged to come use the library’s resources themselves. Anna sometimes spends more time on interesting queries if they offer opportunities to enhance her own knowledge.

At the Science Museum, where Anna has a small basement office, she hopes to complete her examination and organization of materials not on display or properly cataloged, and then to develop new exhibits and attractions on the museum floor. The building is packed regularly with large groups of schoolchildren, but more often other exhibits seem to attract them and their teachers. That certainly is a troubling issue not confined to this public horological collection.

My recent visits to the museum included a tour with Jane of the new exhibit Science City that she had a major hand in creating during the past five years. It is permanent, meaning that it is expected to remain in place for perhaps 20 years. It fills the larger portion of the building’s second floor, complementing the adjacent horological displays. She co-authored the accompanying book, subtitled Craft, Commerce and Curiosity in London 1550-1800. She wrote three of the book’s chapters including Chapter 1, “A New Trade in London 1550-1650,” which showcases sundials and a circa 1600 drum table clock by Nicholas Vallin. She especially wanted me to view a clever life-size diorama of the 17th-century workshop of instrument maker Elias Allen (d. 1653), the first such London craftsman to make his living solely by this trade. Most intriguing in the display was a circa 1700 sundial-making tool, although obviously it was not one that Allen could have used.

Hardly resting on her laurels, Jane now is preparing a temporary exhibit at the museum on Greek science. Like Anna Rolls, she also was elected in spring 2019 to serve on the Council of the Antiquarian Horological Society. I did not have an opportunity to ask if she is descended from an earlier Jane Desborough (1606–56) who was the sister of Oliver Cromwell.

Ten miles down the Thames River is the Royal Observatory Greenwich. Here on the prime meridian, where visitors can worship John Harrison’s and Larcum Kendall’s chronometers, is where I spent a day with the two other women I am featuring.

Emily is a proficient practical horologist, having learned clock- and watch-making, conservation, and restoration, at the Vakschool Schoonhoven, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp, and the Universiteit Antwerpen where she earned a Master of Arts. During her practical training, she realized that she was greatly interested in the history of these objects as well. She now is responsible for all the magnificent timekeepers at the observatory, from rows of marine chronometers inside at ground level to the rooftop time ball. Everyone interested in horology should visit the ROG website and make the pilgrimage to Greenwich in person.

At Kidbrooke, Daniela passed us through the locked gates and doors and into her spacious “small objects” workshop studio. An imposing tall clock was in process, as were other items needing her expert attention. She also walked us into a few other conservation studios where gilt frames were being repaired and where a dress uniform and two wigs of Lord Cornwallis were receiving treatment. The wigs, with shorter brown hair rather than the long white powdered hairpieces we expected, had required nit removal; fortunately, all those infant head lice had died long ago.

We also visited the adjacent row of smaller buildings used for collections storage. We entered one and then an interior windowless room lined with important tall clocks awaiting study and cataloguing, conservation as needed, and perhaps future display (we hope).

Daniela began her craft studies in jewelry but switched to studying horology at West Dean College. Tuition costs there are steep, but she was greatly assisted by grants from the George Daniels Educational Trust as she completed the two-year course of study. She also was aided financially by the York Foundation for Conservation and Craftsmanship, and she received the West Dean Conservation Award from the Worshipful Company of Arts Scholars that, in her words, “Gave me an enormous boost and further confirmed my commitment to this disappearing craft.” She, too, appreciates the history of the objects she works on, describing how she was torn at West Dean between the school’s workshops and library, both open and beckoning every day.

All four of these women have achieved the goal of museum work at a time when such jobs are scarce and highly competitive. Arriving in those coveted positions required each of them to devote years of hard dedicated work and commitment. They recognize that not everybody, man or woman, can put in the time or has the proper temperament for such careful and focused labor. As a professional working horologist for more than 30 years, I certainly understand the challenges they have faced, although I always have worked independently as a sole proprietor, never for an institution except on a project basis. Working alone was a possibility for Anna, Emily, and Daniela, but they preferred receiving a steady paycheck and avoiding the many pitfalls of running one’s own small business, especially in England where regulations are tighter and competition is keener.

By wonderful coincidence, I did meet two other young women during my week in London, each of whom contacted me within a week before my flight to England. Unknown to one other, they were intensively studying centuries of fine art images with clocks and watches. This of course is one of my own longstanding interests that resulted in my 36 “Horology in Art” articles in this magazine and the 2017 NAWCC symposium I organized at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Pauline Wholey, an undergraduate student at City, University of London, chose the topic for her senior year thesis. She has clocks in her blood; her Dutch grandfather owns an impressive collection of them. Christina Faraday, Affiliated Lecturer in History of Art, University of Cambridge, is writing a chapter on the subject for a forthcoming large-scale General History of Horology to be published in 2021 by the Oxford University Press. The tome’s editor, eminent horological scholar and bookseller Anthony Turner, informed me that the book will have 44 chapters, 40 authors, 200 illustrations, and close to 1,000 pages. If I can lift it, I will buy it when it appears.

London of course is not the only home for women in horology, nor is this article the only treatment of the subject. However, I hope that this is informative and instructive. Other important women will be speakers at the “Horology 1776” symposium. Jenny Uglow, a highly respected and widely published British historian, will deliver our James Arthur Lecture. Mary Jane Dapkus, familiar to Watch & Clock Bulletin readers and her scholar colleagues, will speak on Masonic clock makers. Dr. Sara J. Schechner will present “Clocks Behind the Enemy Lines”; she is the David P. Wheatland Curator, Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, Harvard University. Her 474-page hardcover book, Time of Our Lives: Sundials of the Adler Planetarium, has just been published and is reviewed in the “Horologica” section of this publication (page 198).