David Christianson’s Timepieces: Masterpieces of Chronometry explores the long history of clock making and horology through a global lens. In this comprehensive piece, he successfully explains clock making over time, allowing the reader to gain a starting knowledge of horology. Christianson explains early in his book that humans first used the celestial clock, the sun and moon, to tell time. These early explanations help to establish the later forms of clocks and how they evolved over time. One of the first clocks is a time stick. The shadow over the time stick provided an approximate time by what interval the shadow was in. Other forms of timekeeping, such as the water clock, or clepsydra, allowed humans to know how much time has passed by how far the vessel sank into the water. The visuals of the mechanics throughout the book are hard to understand for the beginner, but clock enthusiasts or makers will revel in the excellent detail about the different escapements.

One of the more interesting correlations Christianson explains is the relationship between religion and clocks during the medieval period. Monks depended on early forms of clocks, such as the hourglass, clepsydra, and burning lamps, for different prayer times. Time was also important to monks and other religious groups because if they were late to prayer, it was seen as taking time away from God. The church also used clocks to determine Easter and other religious holidays. He provides excellent descriptions and visuals to show the types of clocks and how they were used, such as sundials and portable compendiums, and to show how diverse and advanced clocks have become since the early uses of sundials. For the horology enthusiast, the visuals and diagrams of the mechanics really emphasize the types of clocks and their advancement over time.

Christianson also explains in great detail how the wealthy and upper classes could only afford clocks during the Middle Ages. Many clockmakers enjoyed royal patronage throughout their careers, thus advancing the artistic merit of clock making. The upper classes also enjoyed artistic clocks in their homes. This helped fuel the growing industry because the clockmaker began to employ specialists in stones, springs, and other pieces in the clock. He also continues to explain the importance of the pendulum and how it transformed many clocks to having protected cases for the pendulum and weights. Christianson provides a list of various scientists and their contributions to clock making to show how each one improved the accuracy of clocks.

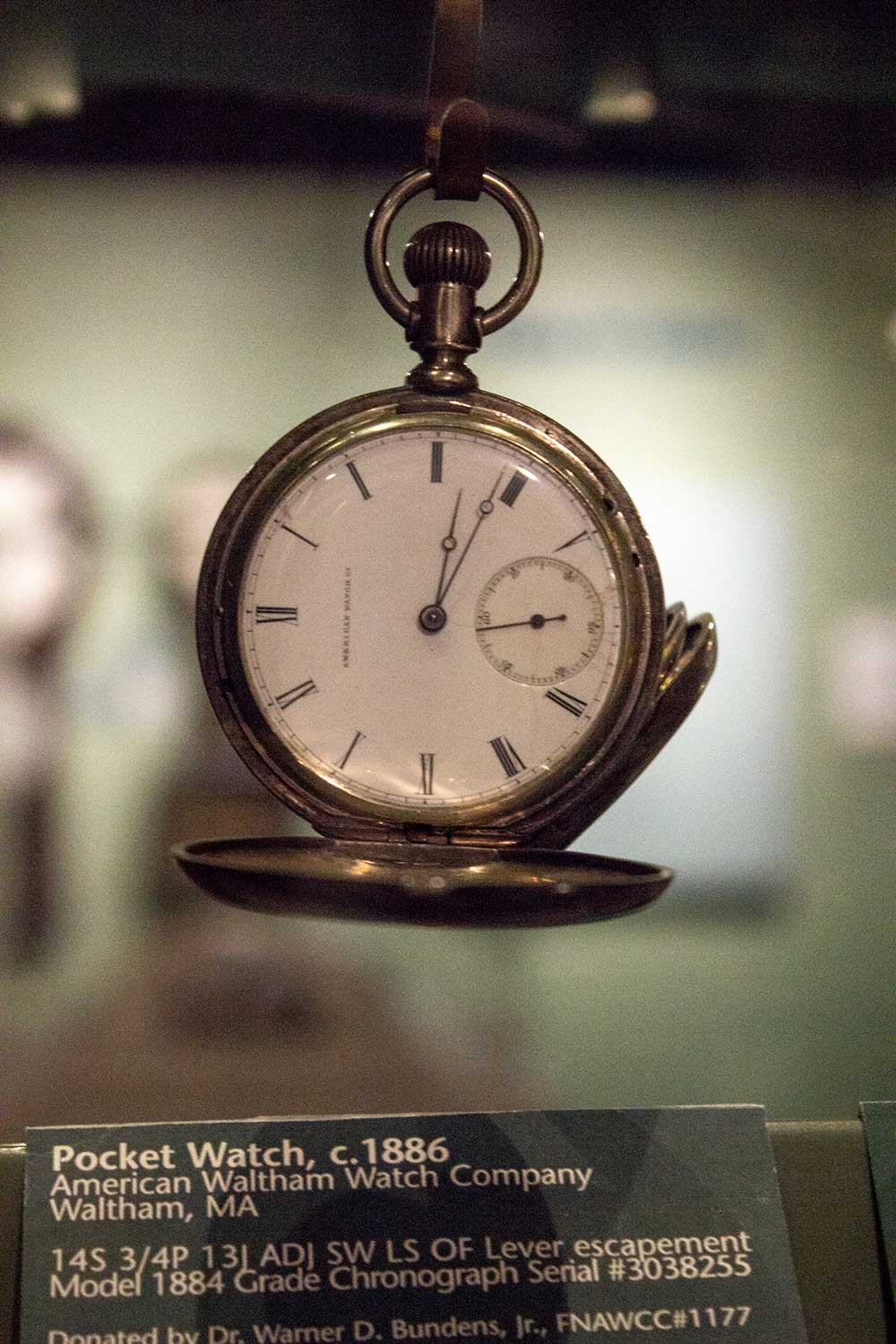

Portable clocks, such as watches, soon became popular in Europe. These highly decorative pieces for the wealthy classes also established a correlation between fashion and the watch. Different stones and gems on the visuals Christianson provides emphasized the extreme artistic detail in many of these pieces. Christianson also explains how the watch’s evolution depicted people’s preference for thinner pocket watches for easier transportation. Many of the thinner pocket watches were made for waistcoat pockets. As the 1900s approached, many watches needed a thicker case for the battery and mechanics.

Christianson establishes that craft guilds are extremely important to the history of clock making. Larger cities in Europe hosted craft guilds in the medieval period, eventually ending in the Middle Ages. This is when Christianson begins to explain the importance of Switzerland in clock making. Although Christianson tries to keep to chronological order, he occasionally jumps from different time periods very abruptly. For example, he explains guilds in the Middle Ages and then explains the industry in the 1960s and 1970s. However, he also explains that the long history of clock making suggests the high amount of detail, accuracy, and merit in the industry.

He makes an excellent argument for the Industrial Revolution and its positive influence on clock making. Mass production and new schedules for workers fueled the need for watches and clocks for all social classes. Swiss watch accuracy and affordability were more popular among the working class. Christianson continues to explain influential people in the Industrial Revolution and their contribution to clocks and watches. One of the more interesting points he makes is that America did not have the clock industry like that of Britain, when America needed clocks during the Industrial Revolution as much as Britain. The introduction of the Waltham Watch Company in America in the late 1800s tripled the production of Swiss companies.

Christianson jumps back to the 1700s and explains the machine age. He explains that alarms were one of the many complications in early watches due to the mechanics. Over time the watch was made smaller with watchmakers adding different details to their artistic pieces. Some crafters added bells, music, and chimes at different times throughout the day. He also provides beneficial information on women in the industry. Unlike many other male-dominated industries at the time, women were frequently involved in the watchmaking industry but were not accepted until the twentieth century during early feminism movements.

One of the last chapters in the book focuses on scientists, such as John Harrison, who helped solve the longitude problem, which eventually led to the development of standard time. He ends the book by describing modern clocks and watches that are more affordable than in the early stages of clock making. The lack of art in modern pieces tells a different story than that of clocks in the Middle Ages: function and practicality are more highly valued.

Christianson provides a glossary for readers to know different terms and parts of the watch; beginners will appreciate this, and veteran clock collectors or enthusiasts will have an excellent reference. He acknowledges that this is a more comprehensive book instead of a scholarly source, which explains the fewer sources. He suggests his sources for further reading. Overall, this is a highly detailed comprehensive book for anyone interested in horology.